Fashion, Algorithms, and the Death of Taste

With Instagram and TikTok's algorithms permanently warping the way we approach fashion, does "taste" exist online? Is the Great Normalization of taste warping what we consider to be "good"?

It’s easy to notice the impact of social media on the fashion scene, particularly in New York City. Everyone dresses well nowadays (yay!) but closer inspection of what you’re seeing reveals an uneasy truth: no matter where you go, there’s an overwhelming feeling of sameness.

This sameness isn’t just in the way that people dress; it’s in the popular clothing major companies produce, what buyers stock in stores, and how pages, individuals, or companies market or share their campaigns online.

Fashion loves a uniform. It loves a trend, glorifies seasonal staples, and adores an easy-but-functional combo. The idea of a uniform predates me (born in 1999), my mom (I’m not allowed to say when she was born), and my grandmother (see my earlier comment), but — through my manic and often over-the-top research — more often than not, I see a uniform of aesthetics rather than one of particular items.

Let me explain with a story. I went to DUMBO with some friends the other week to check out some jeans (good jeans, bad available stock), and kept encountering people wearing the same things despite being wildly different in appearance.

The modern uniform for men shouldn’t come as a shock to any fashion-obsessed person. It goes as such: vintage pants (faded in just the right way), a vintage tee (cropped to perfection and with a few tasteful-but-not-trashy holes!), and a rotating set of similar-but-not-the-same shoes/hats/belts/etc.

Did I miss a memo? Take a look next time you find yourself in a group of 20 to 34 year olds: while the colors, patterns, and brands change, there’s a lot of the same thing.

Fashion — particularly vintage and “archive” fashion — is a way to distinguish oneself from everyone else. However, if everyone’s unique in the same way, everyone ends up being the same.

I spend a lot of time thinking about why fashion — particularly men’s fashion — is the way that it is. I read a lot of books, people-watch like a hawk (style report coming next week!), and talk, incessantly, about it to anybody who feels up to engaging.

Further, I’m also a child of the internet. I remember the last gasp of dial-up, AIM Messenger, computer games coming on discs, the early advents of YouTube, Limewire, SoulSeek, Napster, Facebook, Digg, and hundreds of other sites. I popped off on early Instagram: I earned ~5,000 followers in 2012 for my tilt-shift photography account.

This is to say that fashion (and internet fashion by proxy) isn’t a recent interest. I found ways to engage online and on Instagram. I was acutely aware of fashion as early as middle school (that’s 2012 for me, ladies and gents) but didn’t know exactly how to interact with it. I spent a lot of time in Urban Outfitters, walking around downtown SoHo with my friend Matt (anybody else remember BLVCKSCVLE?), and trying, desperately, to buy the item-of-the-week at Supreme. My biggest get was a 2012 Supreme X CDG Box Logo, which is still stashed in the bottom of a plastic container in my mom’s condo.

I checked this past week and couldn’t find it. I think I may have sold it for a pair of Yeezy 350s back in 2017. Oh well.

I can say, both anecdotally and empirically, that there existed distinct tastes of the fashion community in the pre-2016 era. The community was smaller. You saw a lot of the same people while roaming around New York. You talked to, read articles by, or saw the same people being assholes on the style/fashion websites.

Very few people did, visited, and wore exactly the same thing: you visited different websites, read different writing, and went to different stores for different things. Each spot had its own distinct identity, its own voice, and own taste, which in turn fed everyone’s distinct tastes (and vitriolic rants on Styleforum).

Taste is as important as it is hard to describe. It’s not a challenge that I face alone in 2025: philosophers pontificated on what taste is and why it’s so desirable as far back as the 1700s.

Voltaire explained “in order to have good taste, it is not enough to see and know what is beautiful in a given work. One must feel beauty and be moved by it. It is not even enough to feel, to be moved in a vague way: it is essential to discern the different shades of feeling.”

Montesquieu continued in “An Essay Upon Taste, in Subjects of Nature, and of Art”, “it is the different pleasures of the soul which form the objects of taste… [these pleasures] may contribute to form the taste; which is nothing else but an ability of discovering, with delicacy and quickness, the degree of pleasure which every thing ought to give to man.” He continued to explain that “natural taste is not a theoretical knowledge, it’s a quick and exquisite application of rules which we do not even know.”

Taste is inherently personal and demands much to cultivate: what do you find beautiful? Why?

Challenging your perceptions of beauty, interrogating your own derivation of pleasure, and thinking about what causes you to like what you like isn’t easy. It’s exhausting to consistently defend your choices, articulate your thoughts, and occasionally admit that yep, I fucked up on that one to others, let alone to yourself.

Instagram, in its current form, offers a safe alternative to the necessary demands of forming personal taste through constant interrogation of one’s feelings. I’m sure you feel — in some capacity — that, there’s a good deal of novel content on the app, it’s all getting to look the same, especially when it comes to fashion.

There’s a long answer to that (one that’s better explained by 300 page books) but the short answer is this: Instagram’s algorithms reward content that appeals to as many people as possible at once. Further the app will, and does, rewards that which sparks a reaction but disincentivizes lingering for too long. Boredom is the worst way for a user to feel while spending time on the app: they might sign off for the day and do something else.

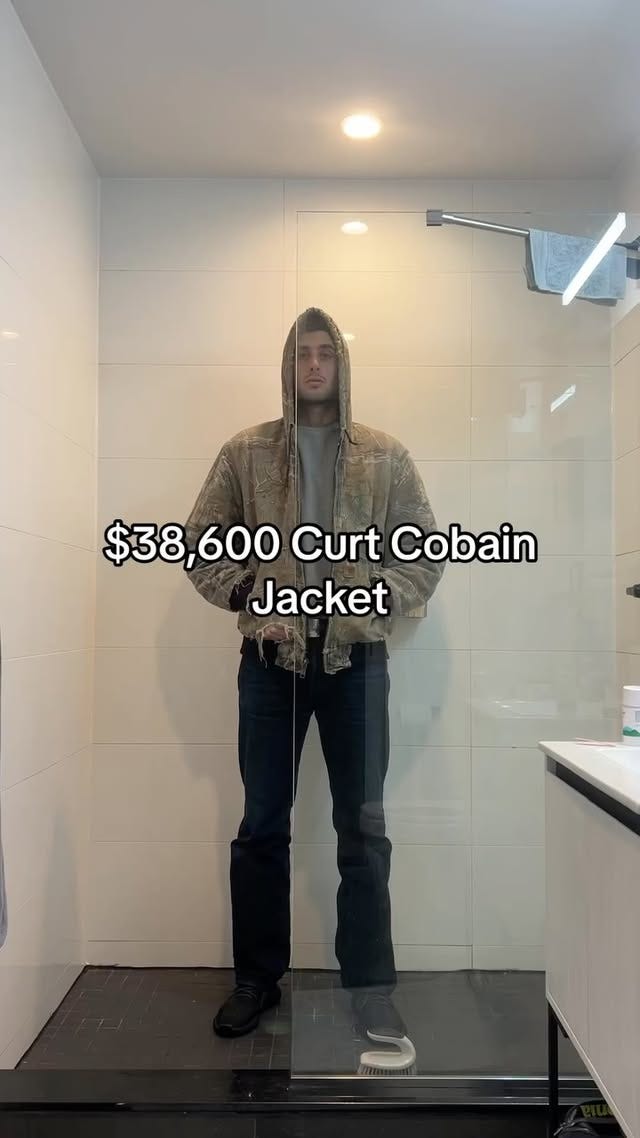

Well-performing content begets other, similar content. Every fashion influencer makes unboxing videos, pack-with-me roundups, and clickbaits with expensive price tags. Those videos do extremely well: my video claiming I spent $40,000 on a Carhartt jacket smashes 2-3 million views each time I post it on both TikTok and Instagram.

This doesn’t just apply to videos. The algorithm coaxes adherence from e-commerce shoots, design, and general clothing construction (evidenced by carousels or single hero images on brand pages). Brands now actively produce clothes, aesthetics, and vibes (yes, even something as ephemeral as a vibe) that appeal to as many people as possible while being just interesting enough.

Let’s make it personal (and juicy). I think the perfect encapsulation of the absence of personality and pleasure in clothing is Our Legacy. I am an ardent OL non-believer: everything they put out reminds me of watered-down Acne, Undercover, or Miu Miu. The brand is the Propel (Gatorade's backwash) of the fashion world, the washouts of the safest and sure-to-sells of other men’s fashion brands.

I don’t think that the brand brings anything new to the table: the button downs, single-pleated pants, and monochromatic sweaters don’t evoke any reaction in me. All of their most popular pieces are the condensation of other, established industry trends or staples: Camion boots are a watered-down cowboy boot, the third cut jeans are their take on the ‘90s baggy-ish denim, and their box shirt uses “all the hallmarks of a classic camp shirt” according to Heddels: an open ‘camp’ collar, straight hem, dropped shoulders, and a boxy fit. Notice what’s missing? Something distinct or disruptive.

This isn’t to say that every item of clothing needs to completely revolutionize the field, but I struggle to find an item, an idea, or even a design choice that feels like a distinct calling card for Our Legacy that didn’t previously exist.

I am completely ambivalent to the brands’ existence, from to the clothes they make, and to any of the messaging or photography campaigns. It’s like asking someone to describe the flavor of ice: there’s just nothing there. I remember very little of Our Legacy when it’s not directly in front of me.

Our Legacy, for me, is fashion’s equivalent of the doomscroll. Do you remember much from yesterday’s time on the For You page? Remember the hundreds of clips you scrolled through? Name fifteen of them. It’s almost impossible! Nothing stays with you!

2016 was the beginning of the degradation of online “taste” in fashion. This has nothing to do with the year itself and everything to do with the introduction of the Instagram algorithm and the resulting departure from the chronologic feed.

In a bid to keep people engaged with a consistent flow of new information (Instagram makes its money on keeping your attention for as long as possible, folks!), Instagram robbed its users of their agency! Previously, all accounts that you elected to follow operated on a level playing field: you saw what others posted most recently and had to make the choice to seek out specific content that interested you. However, the shift to algorithmic-proffered content forced users to see what the algorithm deemed as most interesting.

What had users similar to you shared, commented on, and liked? What post would most likely capture your attention and provoke a reaction? What would keep you swiping?

Writer Kyle Chayka describes the departure from human-curated content and rush towards algorithmic-dictated feeds in his 2024 book, Filterworld. He points to these feeds as eroding the sense of self (virtually and in real life), flattening culture, and rewarding only the most palatable. A particularly poignant paragraph of his stayed with me:

“While [the shift towards algorithm-dictated content serving] has lowered many cultural barriers to entry, since anyone can make their work public online, it has also resulted in a kind of tyranny of real-time data. Attention becomes the only metric by which culture is judged, and what gets attention is dictated by equations developed by Silicon Valley engineers. The outcome of such algorithmic gatekeeping is the pervasive flattening that has been happening across culture. By flatness I mean homogenization but also a reduction into simplicity: the least ambiguous, least disruptive, and perhaps the least meaningful pieces of culture are promoted the most.”

Previously, I didn’t have the words or explanation for the Great Normalization of culture (and fashion). I knew, anecdotally, that everyone was seeing the same stuff, interacting with the same trends, and buying the same items. I explained in an earlier post how brands cracked viral marketing by ensuring that everyone was wearing the same item and noted some of the PR-pushed items in a style report.

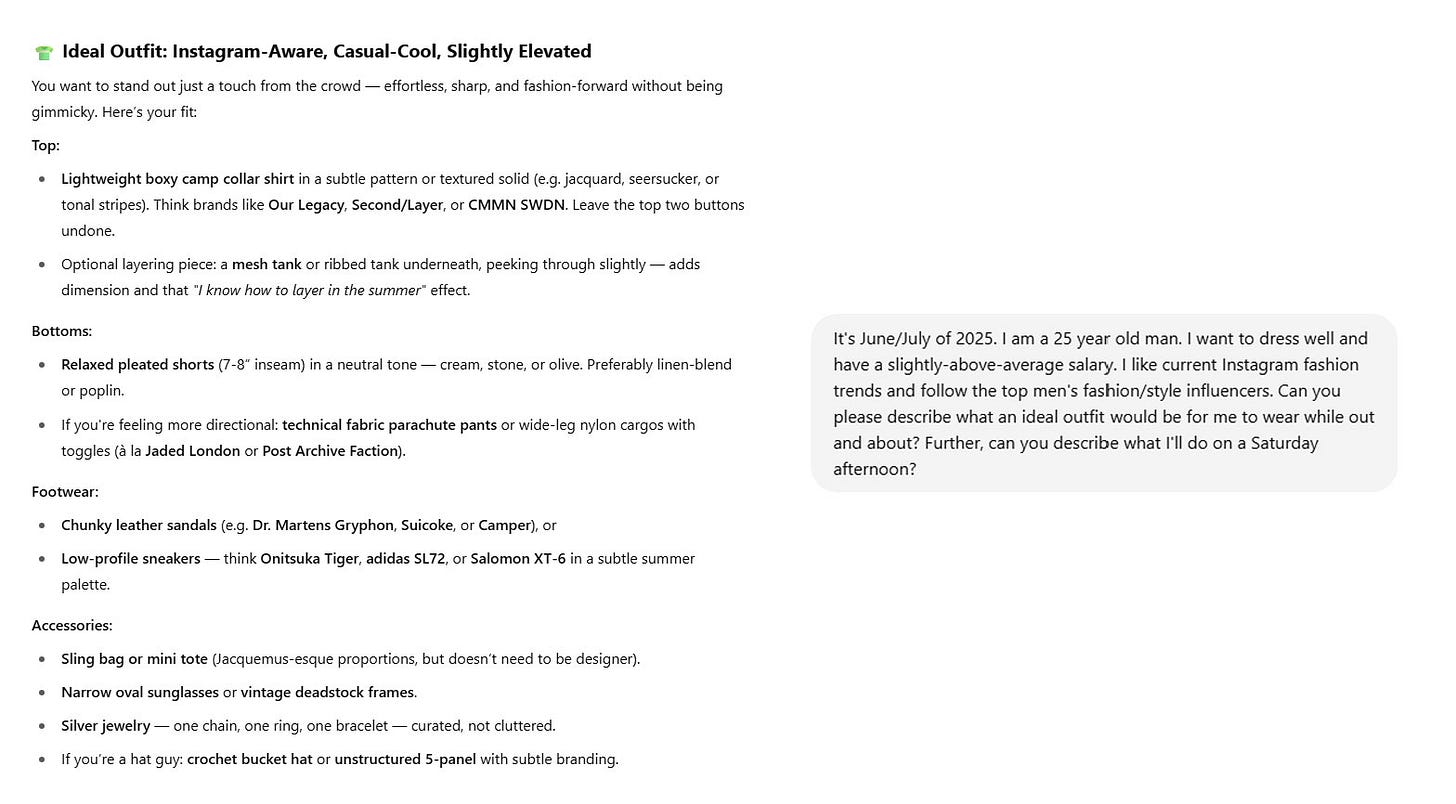

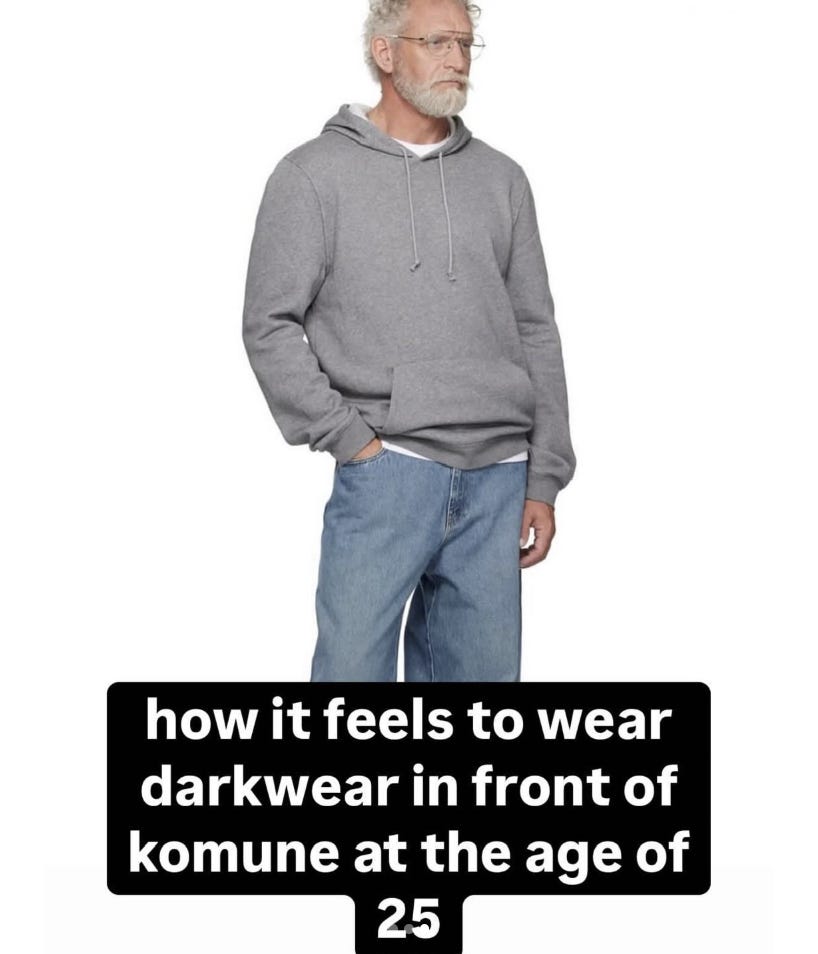

This also rings true for some of the most popular fashion brands today. I am vehemently opposed to using ChatGPT in any capacity for my writing, but believed it would be the best way to capture the current algorithm-zeitgeist. I prompted it to explain an “ideal” outfit. Here’s what it spat:

I want to be very clear before anyone calls me a hater. Nobody’s dressing poorly. We’re in a golden age of the “average dude” dressing out of his mind when compared to the 2000s or 2010s. However, there’s absolutely a flattening of fashion… a reduction into sameness.

I got to thinking: was this different to the culture I experienced in SoHo in 2014? Everyone in that Supreme line followed the same accounts, checked (mostly) the same websites for drop news, and dressed in the same few brands.

In some ways, nothing’s changed: there are still homogenous groups of fashion-obsessed teens and 20-somethings wherever you look. They still find spaces to converse online, take fitpics, and follow — generally — the same people online.

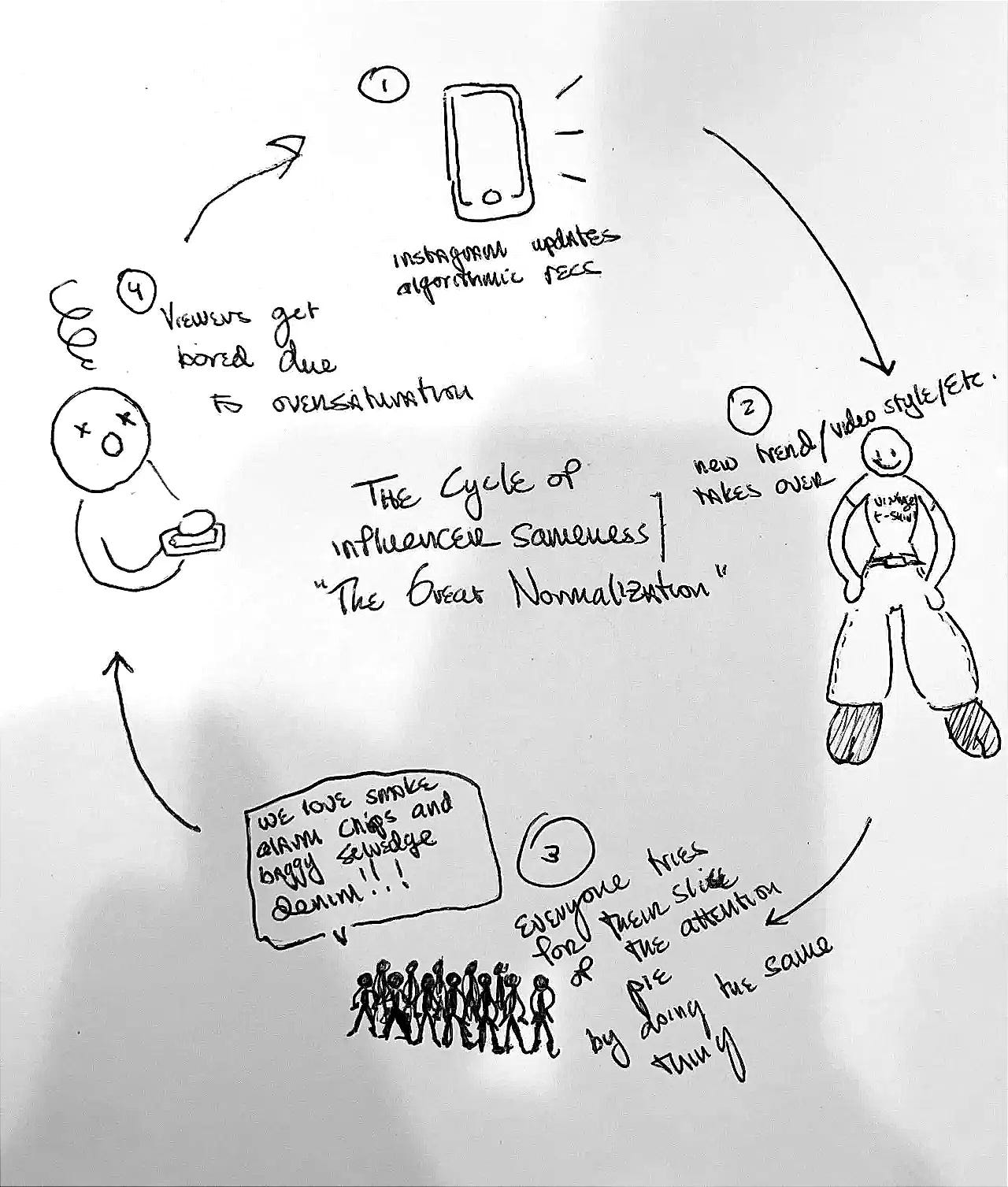

In other ways, everything is different. There are no longer different forums, different websites, or different spaces for these groups to converge. Most groups find themselves on Instagram, TikTok, or Discord. Small brands don’t have their own stores anymore and instead find themselves rolled into larger boutiques (I’ll touch on these later, I think these boutiques rock!). Influencers are bigger and blander than ever. It’s all a massive cycle, as drawn by yours truly in the library where I’m working.

This flattening and blitzing toward the Great Normalification on Instagram in particular caused the burnout we’re currently seeing. Influencer acquaintances of mine saw their views plummet from the hundreds of thousands (consistently!) to the mid-hundreds to low thousands as they struggled to distinguish themselves from an increasingly saturated competition.

Many of these influencers compete for the same deals, hang out at the same places, and wear the same types of things — their taste, in some part, is dictated by their audience (and thus, the algorithm). The practice of consistently responding to what a virtual audience engages with can only drive you toward what is palatable to the largest audience possible: the real-time result of the Instagram algorithm.

Thus, personal style, now more than ever, is less present in fashion. How many of us defer to the algorithm for fashion-related content? How often do you actively seek out someone in particular for their recommendations and can ensure those recommendations aren’t being made by a company? Are those recommenders free from algorithm-brain themselves?

As an insider: No, they aren’t. It’s why — in my opinion — we see so much Our Legacy-type clothing. It’s also ironic to see videos about how to “find your personal style” advocate for going deeper online and participating more in the systems that actively rob people of their ability to discern what they like for theirselves.

Want to have a “personal style”? Get offline. Develop a hobby. Find clothes that serve those desires, those activities, and your life offline.

You can also rely on others for their tastes (many places make their money on having good taste!). Boutiques are a great place to start. I love talking about Komune (and am an ardent supporter of theirs) and think they serve as a great example of how we get out of IG-pilled cottonmouth and into the yummy meat-and-potatoes of what the fashion community should be.

The store is constantly changing, constantly updating their selection, and constantly evaluating what could do well. It’s obviously within the owners’ — Martin, Lia, Cassie, and Brandon — best interest to consistently display exciting, tantalizing, and engaging clothing. They have rent to pay and a payroll to meet. However, they don’t have an incentive to sell what everyone else is selling; they’d be intentionally creating competition within their vertical.

Orchard Street is a fantastic place to go to both see the algorithm at work and free yourself from the (online) Great Flattening™. Stores (for the most part) on the street don’t look the same and don’t sell the same stuff. Self Edge doesn’t sell the same stuff or look like Desert Vintage. Kartik Research doesn’t look the same or sell the same stuff as TUMBAO. Komune doesn’t look the same or sell the same stuff as Lara Koleji. All of these stores are run by people whose livelihoods depend on being distinct and curating products that stand out from their peers.

As a quick aside, there are a LOT of algorithm-dressing 20-somethings on Orchard Street nowadays. I’m not implying that you won’t see them.

Back to the topic at hand: Let’s compare two stores — with similar approaches and business models — and examine just how different they are. We’ll start with 2nd Street.

If you’d like to see the algorithm at work, pop into a 2nd Street. I’m serious. There’s no identity in the stores. They buy and sell anything with a designer label. There’s no discerning eye that says yes or no: they eschew taste for stock.

Further, the flatting that we see online is clear when you walk in. Shoppers mostly dress the same. The same items get bought and sold and endlessly recycled through the multiple locations in the city. The items-of-the-week (Tabi mary janes, Balenciaga denim jackets, ERD Tees, etc.) pass from fashion dude (gender-neutral usage of dude in this case) fashion dude in an endless cycle: one in which the only winner is 2nd Street.

This makes sense, unfortunately. It’s within the company’s best interest to increase the churn, to stock what makes money and will sell to the “normal” fashion buyer. The 2nd Street corporation has over 1,000 locations worldwide: it’s impossible to keep taste or an identity in the equation when scaling a company at a meteoric rate.

On the other side of the same coin is Luke’s. We had Luke on the podcast a few months ago: he’s brash, ebullient, and knows his shit. His buy-sell-trade shop constantly mows through stock, but there’s a very clear identity to the store, made clear by the Instagram and made even clearer as you walk in.

The store oozes with personality (and clothing). All the tags are lands from Magic the Gathering. There’s a rotating selection of shorts, pants, and weather-appropriate bottoms. Everyone who works there knows their stuff, and knows what they’re in the market for (and what shoppers are buying). It’s the employee prerogative to buy the most desirable stuff, and I rarely see junk in Luke’s store, save for the rare Bode jacket (fuck Bode).

Although it’s smaller, Luke’s competes with 2nd Street not on overall volume, but on taste. The chance I walk into the former and see something interesting (not necessarily something I’d buy, but something that strikes my own fancy) is much higher than the chance of seeing something interesting at the latter.

The curation is why Luke’s store works, and why it’s doing so well: the same can be said about any one of the curated vintage mainstays of the Lower East Side. The shops might not have items that appeal to my taste, but they were selected with taste.

There’s also the fallacy of believing you’ve developed your own taste after appropriating someone else’s, but that’s another Substack for another day. Everyone at a Colbo event dress the same, most people at Komune events dress the same… there’s a nuance to having a personal style shared with others versus being consumed by an aesthetic.

So, reader. What do you like? What does your personal taste speak to? Can you articulate it?

If your answer is anywhere from yes to no, I encourage you to go outside! Go to clothing stores. Talk to people. Go observe what people are wearing and get inspired. What you see is not always going to be interesting, and that’s alright.

Let yourself be bored.

It’s not always going to be good, which is even better! Let yourself be disgusted, revolted, insulted, and upset by clothing, but don’t you dare shrug something off when you’re having those reactions. Hold those emotions close, articulate why you’re feeling them, and let what you dislike guide you to what you like.

I’m fully aware that not everybody reading this article has the privilege of living in New York — believe me when I say that the most interesting fashion happens outside of the cities (take, for example, my adoration of the river guide “uniform”).

Develop your taste! Read books, go dance, party your heart out, play video games, fall in love, look for fun outfits, and look at art: just don’t do it online.

Good read! A lot of stuff to contemplate.

I'm wondering what your view is in terms of how you define that distinction between people having a personal style shared with others vs. being consumed by an aesthetic.

Do you think that when people choose to dress in this uniform styling, they're participating in the world as people who are trying to attach themselves to fashion as a concept? Because I feel like a lot of uniform guys kind of approach this form of dressing with only so much engagement. The people that are "into" fashion WOULD move further into directions that are unique to themselves, while most of the others utilize a simple, effective base in order to have good social capital on their side. The disappointment comes from the idea that it's harder to parse which is which if some core elements you appreciate are lost in the weeds of content farming wardrobes, but that feels like the natural progression of any subculture unfortunately.

Good read, but I agree with the above commenter that people who enjoy fashion and want a personal aesthetic will evolve past this, those who don’t- won’t! I follow a lot of cooking content and it can be the same- there’s a certain set of ingredients (herbs, preserved lemon, harissa, celery, anchovies) that it seems like everyone is into now. But some people are genuinely interested in food, as opposed to the people who see “having good taste in food” as a lifestyle & aesthetic goal. They might all start in the same place with cooking and entertaining, but the ones who are genuinely interested will move on to finding a way to cook and entertain that fits them, rather than always emulating what fits Alison Roman. And, similarly to your example of the perfect, well-worn suit, you can’t always tell the difference just by meeting them or eating a few meals— but you absolutely can if you know them well.