Systematic Racism Birthed Ivy Style. 60 Years Later, There's a Custody War.

This week on One Size Fits All, I explore the conditions under which Ivy Prep developed, why it matters, and who — in modern fashion — owns the look.

Hi friends!

I’ve got some fun articles coming soon — Worn to Death, my in-and-out lists, etc. — but I want to continue flexing my writing muscles with some heavily-researched longform pieces.

This week, I’m going to examine the conditions under which Ivy style developed, how and why it evolved, and the recontextualization of its cues in modern fashion. I’m consistently frustrated by the coverage of prep, which largely ignores the racial and socioeconomic context of its development, as is clear in this GQ article.

In my discussion, I focus quite a bit on Yale — this is the school I’m most familiar with, as I earned my undergrad degrees there. This ongoing focus is a result of my familiarity rather than any uniquely relevant history, especially compared to its other, oftentimes more historically racist, Ivy League counterparts.

Strap in! It’s going to be a heavy one. As always, if you want to support the Substack, subscribe (it’s free!), share with a friend, and have a conversation (either with me or a friend!).

I’d also like to thank Lindsay Jost, my friend and trusted editor, for going through this piece with a fine-toothed comb and making it grammatically sound.

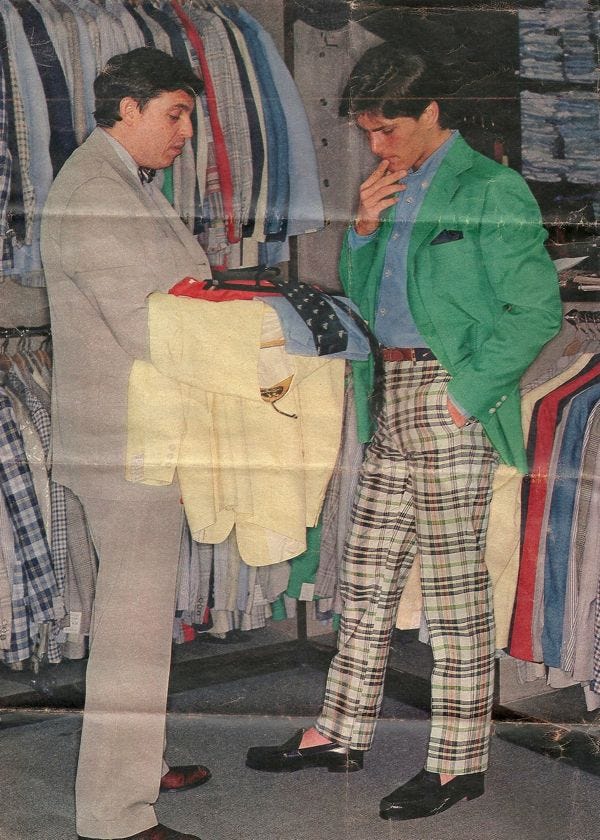

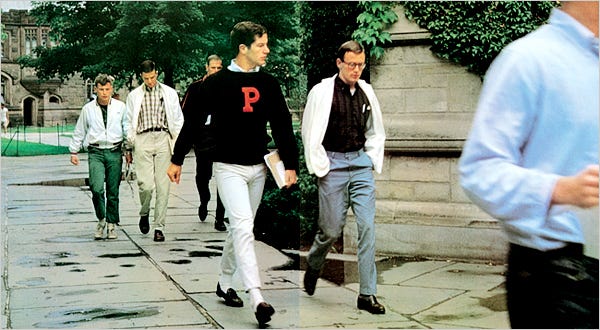

The Ivy style should be explained here for those unfamiliar with the term or the distinct look. The look is Put simply: take the best-dressed kid at a Connecticut or Massachusetts Yacht Club (who also happens to be the starting quarterback for his high school football team), and you’ve got it. Ivy League students emblematic of the aesthetic (which was formed post-WWII and pre-1964) are clearly wealthy, athletic, confident, and all smiles as they stride from class to class in hundred-dollar penny loafers.

The men pictured are clean-shaven, square-jawed, and bespectacled — the consummate professionals on their way to careers in science, philosophy, or mathematics. WASP-y activities are lauded and signaled by the clothing choices made by these men: "A rubberized sailing parka is the ultimate in rugged outerwear that can be worn not only on a stormy sea, but also on a rainy day or for playing sports.” Truly, the ideal Ivy man not only excels in the classroom, but works and plays in the upper echelons of American society; he belongs to a yacht club, provides for his family, and is clean-cut and professional in all aspects of his future white, upper-class, suburban life.

How do looks like this develop? Distinct fashion styles are birthed by exclusive groups or spaces. The exclusivity of said groups provides a breeding ground for ideas and culture, consolidating a group identity while insulating from outside input, dissenting opinion, or watering down the core tenants. Just as radicalization in thought or action develops in exclusive groups (see the flywheel of right-wing, nationalistic paranoia leading to the wide-scale acceptance of the alt-right in international politics), the growth and strengthening of a core identity within these groups demands a visual identity to signal membership to other members in the know.

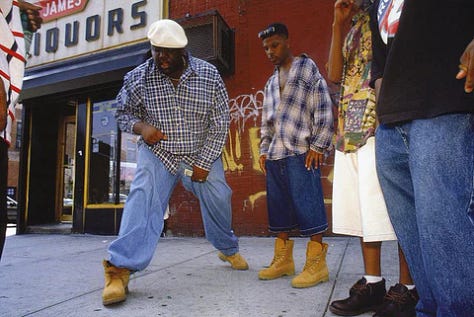

It’s important to acknowledge that this relationship between exclusive groups and visual identity can be found in any exclusive group: Wall Street and finance culture of the 1980s gave us the Rolex-wearing, Armani-wrapped, smooth-talking monsters of American Psycho, the budding rap scene of the ‘80s, ‘90s, and 2000s gave us baggy jeans, oversized jerseys, and a variety of shoes (oh, so many shoes!), and modern fashion communities facilitated by purely virtual interactions birthed a generation of gorpcore-rocking, Rick-Owens-obsessed teenagers too esoteric to be understood by anyone outside of the know.

It follows that, when an exclusive space develops, so does a shared identity — one that is then symbolized or manifested in the clothing options of said space. Fashion serves as an indication of membership, a commitment to the ideals, and a statement to those outside of the group about the validity or authenticity of your movement — consider the Black Panther movement of the late ‘60s and ‘70s, the hippies engrossed in San Francisco’s 1967 summer of love, or the crust punks of 1980’s England. Groups are more likely to be recognized as groups and/or taken seriously if there’s coordination between members. Further, willingness to participate in group culture, through clothing as well as lifestyle, thought, or occupation, furthers a member’s psychological commitment to said group.

So: why does this matter to Ivy prep? Well, there’s a lot of discussion today about preppy or Ivy Trad style, but nobody’s talking about the historical context. Writers acknowledge the people who created the style, but don’t fully elaborate on the conditions under which the style grew.

Moreover, the far-right and far-left seem to be waging a war regarding ownership of oxford shirts, Bass Weejuns, and tweed suits — do the seminal loafers belong to the likes of Young Republicans from Connecticut or left-leaning 20-somethings in the Lower East Side? Who wears them better? Who gets to ‘own’ the style?

I’ll explore and answer these questions later in the article, but I think it’s important to first understand why these styles developed in the way they did, the historical context surrounding the Ivy League, and the mythos surrounding the birth of Ivy Trad style.

Ivy League schools are, inherently, an exclusive space. At the time of their applications and throughout their college experiences, students are required to excel in academics, athletics, extracurriculars, and business. These institutions want to be sure that their students graduate, achieve success in industry, and, in turn, donate to the school, send their children (if possible) to their alma mater, and add to the lasting legacy of greatness of the institution.

While acceptance rates to Ivy League schools today fall in the low single digits, conditions in the first half of the 20th century furthered this exclusivity. Students were not only required to meet or exceed expectations in all aforementioned categories, but also meet strict racial, religious, and socioeconomic profiling to secure admission. Many of the Ivy League schools — particularly Harvard, Yale, Princeton, Dartmouth, and Penn — held clear visions of their ‘ideal’ student: northeastern, well-educated (usually graduates of elite Northeastern prep schools like Exeter, Hotchkiss, Choate, and Taft), wealthy men, who were preferred by both society and the admissions boards of the universities they eventually attended.

These visions were enforced systematically and socially, with rules, standards, and quotas crafted among the high-ranking members of the universities ensuring the consistency of their student populations and maintaining the dominance of WASP students.

This began with university and federal policy. In the eyes of the United States, not all men were created equal (which says nothing about the women, mind you). Each of the schools I’ll discuss has made strides in accepting a more diverse class and has certainly improved compared to the 1960s, but the historical exclusion of persons not deemed the ideal is not ancient history.

This legalized discrimination was in practice as recently as 50 years ago. Yale University — my alma mater — only began accepting women in 1969. While Yale admitted its first black student to a medical program (Cortlandt Van Rensselaer Creed) in 1835 and its first PhD student (Edward Bouchet) in 1876, black students saw little or no admittance through the Jim Crow era in both the undergraduate and graduate programs. Further, not a single black student was admitted to the medical school from 1900-1945.

These exclusionary practices weren’t exclusive to Yale. Harvard remained socially segregated (if not fundamentally segregated) through the 1960s, as black students were rejected from dorms, finals/eating clubs, and social events. Women were allowed admission into the undergraduate population of Harvard in 1975 after previously being siloed into Radcliffe College, a school created specifically for women gated from Harvard (these schools were not completely merged until 1999).

Princeton was famously one of the most anti-Semitic Ivy League schools (Yale, Harvard, and Dartmouth were known for having informal caps for Jewish students through the ‘50s and ‘60s), with director of admissions Radcliffe Heermance utilizing a quota that limited Jewish admissions to 4%. Further, Princeton did not admit black students at all until World War II, with the first admitted students coming as a result of the Navy V-12 program aimed at bolstering falling college admissions.

As previously mentioned, the exclusion of minorities wasn’t gated to university policies. To be an Ivy Man was to exemplify the “American ideal”, especially important for the country and for the universities in the wake of World War II. The 1924 Johnson-Reed Act, which enshrined a deeply racist immigration policy that prioritized Anglo-Saxon and Nordic immigration to the US and actively discriminated against “undesirable” populations (read, people of color, especially Asians) was overturned in 1965 when President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Hart-Celler Act, which eliminated the racist policy of limiting immigration based on national origin.

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 (particularly Title IV, which encouraged systematic integration in schools), Executive Order 10925 (which introduced affirmative action), and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 began the process of ending discrimination against minorities.

Alongside this systematic discrimination in federal, state, and university policy, covert racism was commonplace in these schools: in the early 1900s, admissions boards insisted on a vague yet firm definition of ‘character’ that served to enshrine and cultivate predominantly white, wealthy, and well-educated Ivy league men.

The idea of a "disparate impact" standard — the practice by which racial barriers are constructed without being overly or explicitly racist — is not new. This line of thought aligns with the historical practice of positioning white men at the forefront of society as a result of their ‘higher level of development, character, and intelligence’ (see racist historical writings like The Bell Curve, which linked intelligence to class and race; Morton’s assertion that white men were the most intelligent as a result of skull size; and the practices of eugenics, eurocentrism, and the Great Chain of Being for more in this vein of racist thinking).

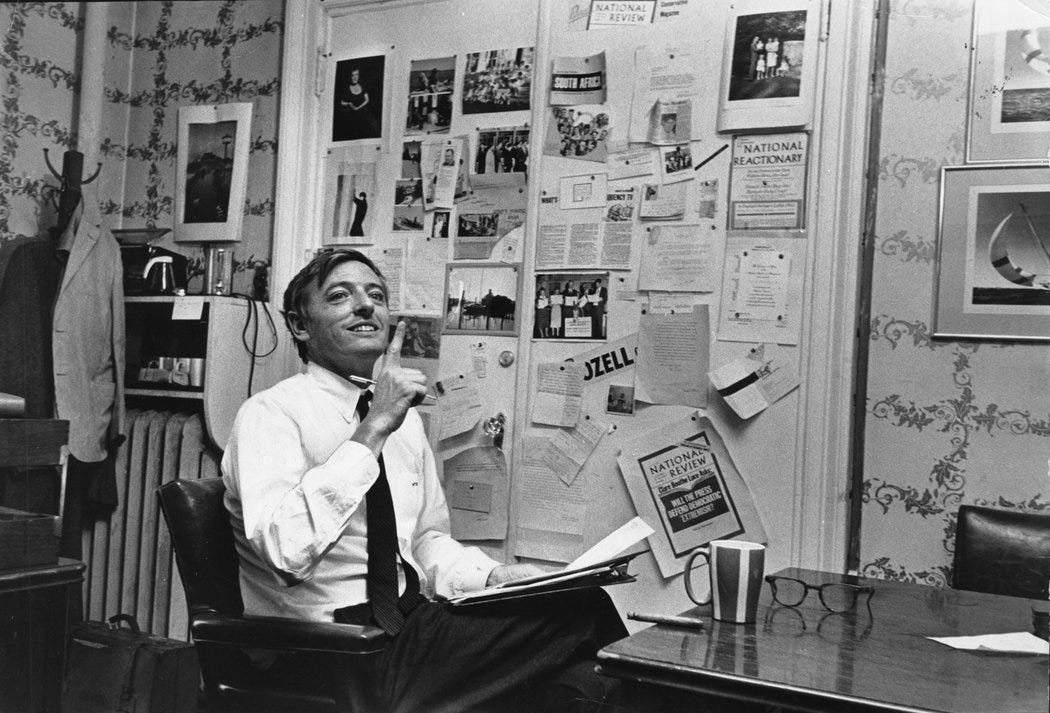

These practices were justified and affirmed by the politics of the university, which emphasized ‘traditional American values.’ Yale was majority Republican through the 1950s and ‘60s. William Buckley (who will come up later in this piece multiple times), arrived at Yale in the ‘50s with the clear mission of advancing the conservative ideology he developed in his adolescence. However, he didn’t have to work hard to change minds: over 50% of Yale students identified as Republicans. Unlike many others, he was Irish Catholic and barely skated through the WASP-heavy admissions process (most likely as a result of his socioeconomic status), but, like many others, he loudly defended the university’s right to practice discrimination in admissions.

In sorting and selecting for applicants like Buckley (wealthy Protestant or Catholic white men from the Northeast) while subtly barring others from securing enrollment, these schools formed an exclusive group, and thus provided the breeding ground for a consistency in thought and distinct visual identity captured in books like Take Ivy.

Interestingly, rather than the campus style or culture developed by the members of the group through consistent and continued participation within the culture, the schools repeatedly accepted students who already fit the mold. Unlike the one-upmanship portrayed in American Psycho or within sneaker culture — perpetuated by those within the spaces looking to signal their authentic participation in said culture — that serve to accelerate the development of the symbolic fashion, the Ivy League schools hand-selected applicants and insulated them from outside influence while also making their exclusive spaces desirable and inaccessible to the majority of Americans.

There is no magic to the Ivy league that bestows its attendees with the je ne sais quoi needed to dress well. There’s no inherent fashion advantage to be gleaned from attending, no ready-to-wear collection left for students on their first-year beds. Rather, Take Ivy and the proliferation of Ivy style were emblematic of the privileged backgrounds of the students and the bigoted practices of the schools themselves.

The Buckley blueprint of a bigoted, arrogant, reactionary Ivy League man (another student’s words, not mine) remained alive and well through the 1960s despite the end of legal discrimination. While systematic exclusion of Jewish, Black, Asian, and other students that did not fit the WASP mold ended in the late 1960s, the social exclusion did not, with these newly accepted students facing ridicule for their cultures, backgrounds, and clothing. Even as black and female citizens gained the legally protected right to participate as whole citizens in society through voting, purportedly equal access to housing, and access to spaces, they remained excluded from truly participating in the Ivy League experience through discrimination in social settings and the lingering spectre of a segregated America.

These imbalances in access and the lasting legacy of the glorification of the WASP-turned-Ivy-Man are clear in the Ivy style. There’s a clear lack of diversity — in race and gender — in the foundational texts and photographs that establish the look. Both the ‘60s “authoritative” incarnation and the newer, “preppy” version of the ‘80s are largely devoid of students of color or women. The ubiquitous and previously-mentioned photobook Take Ivy, released in 1965, serves as a reference point for the style and captures the discriminatory Ivy League: only five women and three non-white men are captured over the 100+ pages. The book comprehensively captures the style at these schools in a pre-integration era and displays the lingering racism and sexism in admissions from the Jim Crow and post-war eras of America.

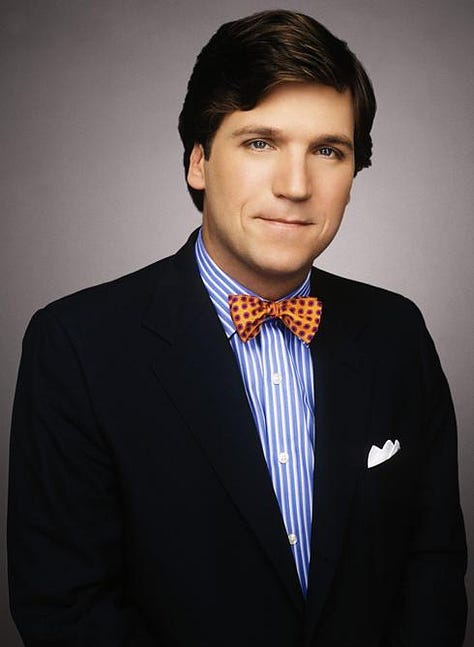

This history of the style explains the romanticization, obsession, and adoption of the style cues by the current American right. Although these politicians decry the Ivy League as bastions of liberal thought and DEI, they still align with pre-integration ideals of the virtuous Ivy Man. These politicians yearn for a time of ‘traditional American values’ and strive to Make America Great Again: a man leading their wives and families as the sole breadwinner, an era where those with ‘character’, ‘integrity’, and ‘grit’ reach wealth and status through hard work. Sound familiar?

Further, the fascist construction of Trump’s party mimics the strategies used by fascist political organizations of the early-and-mid 1900s (Nazis), in which the party 1. believes in the superiority of certain individuals or groups 2. extolls ‘traditional values’ (with or without historical precedent) 3. persecutes other groups while bemoaning the systematic dismantling of their own peoples (who hold power over the persecuted groups) and 4. cleanses those deemed not to belong (often minorities, ‘undesirables’, jews, women, etc.) as described by Ian Kershaw in his book To Hell and Back.

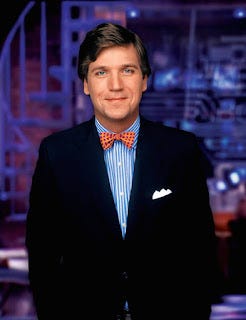

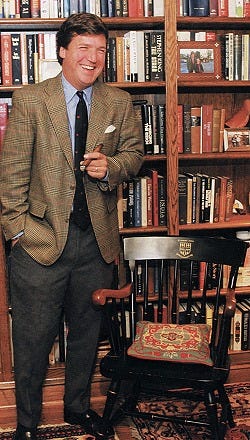

By aligning their values, goals, and politician plan with the style of Take Ivy, Republicans align with the Ivy League men of pre-1965; ending affirmative action, dismantling DEI initiatives through the end of federally funding for schools that maintain race-based programs, and attempting to control university governance and curriculums to eliminate “wokeness” and “leftist indoctrination.” They affirm their status as the good old boys, superior to those (read: to all but other white men) through their clothing: Ivy-educated, wealthy, virtuous men who worked their way to success (however false this reality actually is). Tucker Carlson, a red-cheeked, bow-tied, khaki-and-sport-coated political pundit aligned himself with the Preppy Handbook’s definition of style. He belies his bigoted views — often repeating sentiment surrounding “demographic replacement” — with a look lifted from a teenage member of a local country club.

His brown tasseled or venetian loafers alongside his choice of L.L. Bean Boots could be ripped straight from the pages of Take Ivy. My own opinions of his style aside (he dresses like shit and none of his suits fit properly) he is taking a page from a time-honored playbook. The worst part? It’s working. He’s built a crowd of people who believe that his brand of bigoted speech comes from a place of education and elucidation. He’s committed to a recognizable aesthetic through an unflinching commitment to a certain style, built an image that softens his inflammatory rhetoric, and builds subconscious associations with said style which serve to compliment his overall messaging and the identity he’s trying to craft.

The style isn’t only prominent in the Republican elite. Remember William Buckley? He’s been enshrined on Yale’s campus in the form of the Buckley Institute, a group that promotes “free speech” in the form of diversity of thought. The group skews far-right, and invites speakers — including Mike Pence, Ben Shapiro, and Vivek Ramaswamy — to campus. The Buckley Institute and its student board strive to confirm the legitimacy of many of these right-wing speakers through invitations to the university, allowing coded, bigoted sentiment under the guise of the first amendment.

Ben Shapiro’s talk on October 7th is a fantastic example of the tactics used by the modern right to skew conversations, use coded language, and to provoke reactions from audiences. Further, the student introducing Ben borrows from the Ivy prep playbook, sporting a freshly-pressed Oxford and khakis as he moderates the conversation. The larger group’s fashion choices align with some cues from the Take Ivy history; Madras shirts, loafers, and khakis are common in the group’s event photos.

I’m not here to lampoon the kids of the Buckley Institute, even if I disagree fundamentally with what they stand for. Additionally, I don’t want to insinuate that the Ivy Trad style rests in the hands of the new-right. It’s actually quite the opposite. Designers and stylists alike have spent decades iterating on the look, recontextualizing key items, and adopting the style for themselves. I’m sure much of the fashion community is familiar with Ametora: How Japan Saved American Style, the seminal text for any workwear-obsessed man looking to justify his trip to Kojima to buy “real selvedge denim.”

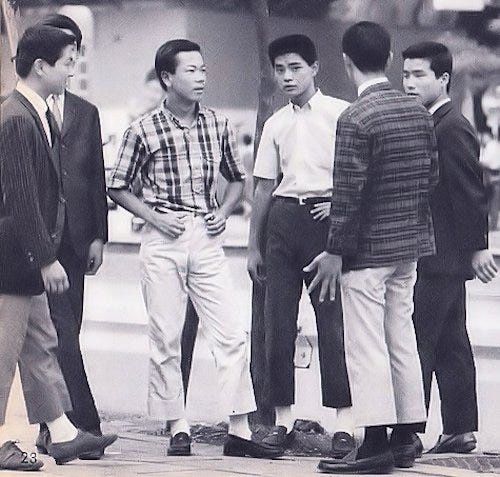

The Japanese adoption — and perfection — of the Take Ivy style reveals the ability of a marginalized or excluded group (in this case, with respect to access to Ivy League universities) to penetrate a previously-inaccessible space through adoption of fashion and elevation of style. To quickly explain how Ivy Style broke out of the US, Kensuke Ishizu recognized the desire for American style in Japan and began importing American culture to Japan in the form of clothing. The Ivy style exploded in popularity after the 1964 Summer Olympics in Tokyo when Japan was trying to prove to the world that they were a much better nation than the one who suffered a massive defeat in the war.

Japanese “Delinquents” were the ones wearing Ivy Trad clothing, but Japan didn’t want other visiting countries to see only these young punks wearing Ivy Style clothing and leave a bad taste. Thus, Ishizu designed Japan’s opening ceremony attire to mimic the styles of the Ivy League: red blazers with gold buttons, white oxford button down shirts, white pants, and white shoes. What better way to show a commitment to a clean-cut, hard-working, high-achieving society than to borrow the apparel of the group that symbolized that in America? The Olympics were followed by the release of Take Ivy, which saw the style explode in mainstream popularity. Japan became both a curator and producer of the style, surpassing the US’ heritage brands in terms of construction and ideation.

So, the Japanese borrowed, perfected, and mainstreamed Ivy style. However, the style made it back to the US in the ‘90s, 2000s, and 2010s and, yet again, were recontextualized. We’ll skip over the Ralph Lauren breed of idolizing the WASP (to keep this article from getting too long), and instead focus on the modern iteration of Ivy Prep within high fashion and among the American left.

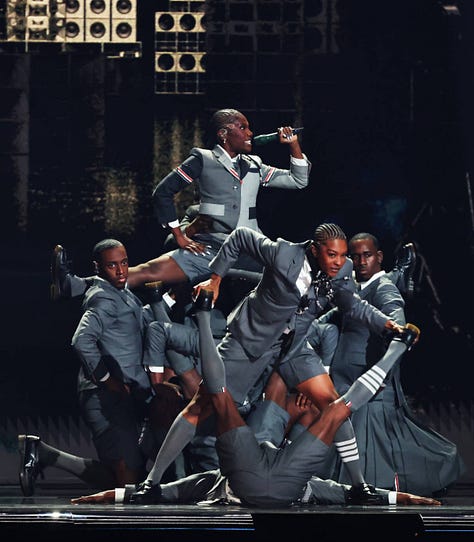

It’s important to note the designers who are pushing the style forward; Thom Browne is very much on the forefront of chopping and screwing these Ivy Prep cues. His FW12 collection in particular (thanks for the confirmation, Mr. Michael Smith) holds a funhouse mirror in front of each page of Take Ivy. Collegiate football players’ muscles threaten to explode from under the seams of their rugby sweaters. Models-turned-monstrosities are adorned in the varsity jackets of ‘60s jocks and glare at the audience. Spikes, studs, and gimp masks are crafted in and around tweed. At its core, the collection (as I interpret it) is about the fetishization of the prep style and the participation by that same crowd in the masturbatory celebration of its own history while also actively subverting the conventions of who owns that style; it’s a fantastic summary of how far the style has come and what it can mean to fashion today.

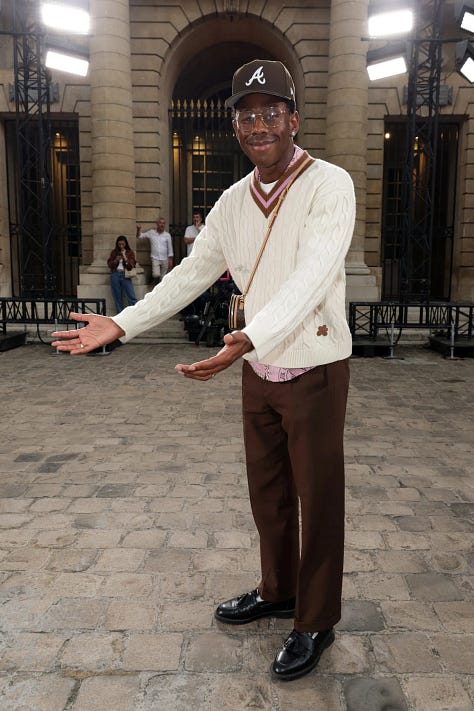

While designers set the stage (again, pun unintended), black musicians and the modern left elevated neo-prep to critical acclaim. Tyler the Creator and his love of preppy items (beginning in 2018/2019 and spread through the Golf Le Fleur line) and Doechii’s recent love of Thom Browne are emblematic of the success, financial viability, and positive critical reception of an elevated, recontextualized prep. Beloved friend Ella Emhoff also rocked Thom Browne at the DNC (a distinctly political stage), flying in the face of the aforementioned old boys club of the preppy American right.

Each of these icons would have been excluded from participating in the style at its inception, but gain power from taking the style for themselves: the symbols that once stood as evidence of discrimination are being sported by those who were discriminated against. While the modern right uses Ivy League fashion to fit into a larger context and signal their intentions, the left turns the Trojan Horse inside out, subverting an old symbol of power and prestige that once acted as a gatekeeping mechanism and is now a vessel for radical inclusion; a sign that those who wear it can and have achieved what was once denied from them.

The recontextualization and appropriation of the aesthetics that once were emblematic of the men benefitting from the systematic oppression of a group of people — in this particular example, non-WASP students — adds to the cultural and symbolic impact of these artists’ work and politics as well as furthering the interconnected histories of music, fashion, and the oppressed. However, even as designers warp the style so far as to be completely unpalatable by those trying to hold onto the origins of the style itself (in this case, the good old boys of the Republican party), the same adoration of that style — or its reclamation — occurs.

I struggled to reconcile my idea of “Ivy fashion” with the reality of attending Yale. Students weren’t wearing looks consisting entirely of penny loafers, Harris tweed, Brooks Brothers, or flannel trousers. The people I did see wearing Brooks Brothers were either frat brothers or Young Republicans walking to meetings of the Tory Party. I saw both men and women wearing loafers at Fence, a coed social group supplanting the conventional fraternity/sorority style. Nobody wore blazers unless there was a formal.

Spurred by the disconnect, I got to thinking: I love watching and noticing and thinking laterally and trying to understand the whole picture. Nothing happens in a vacuum. If you know where to look, who to look at, and when to start looking, you’ll be able to notice things that make it clear that history is not isolated to the past and that our future is happening in the now. It feels apt that a style borne from systematic discrimination is being pushed — however loudly — to the front of American pop culture and politics when the majority of people have forgotten the conditions of its inception and growth.

The battle over America is not only being waged in Congress, the House, and the Oval Office; it’s fought on the streets, the suburbs, and on social media. People will need a way to signal their allegiances as the lines are drawn in the sand. Clothes aren’t just clothes (a refrain you’ll hear from me time and time again), but clear indicators of personality, activity, and politics. It’s not my place to tell people what to wear, but it is my place to comment on why we wear what we do and how those clothes came to be. Future politicians and aspirational figures are going to mold our futures in the echoes of Ivy Prep — it just remains to be seen who’s going to be wearing the Harris Tweed when the dust settles.

INCREDIBLE, SOL!!!!

Tucker Carlson is handsome, his mother was a talanted left leaning artist. Ella also look phenomenalz I believe this style has been intertwined since the beginning. The driving loafer was referred to as “the artist shoe”. My grandpa said back in the day all blacks wore suits..The shift towards this attire now is because we’ve been wearing sweat pants/sneakers since the pandemic and the pendulum is swinging to the opposite + Not everything is about race.